By John W. Travis (MD) &

John V. Geisheker (JD, LLM)

Published Friday, 30 May 2008 in

Kindred Community

Doctors Opposing Circumcision (D.O.C), an international physicians' charity, fields around three anguished complaints each week from parents of intact (not circumcised) boys whose foreskins were retracted by ignorant medical practitioners.1 Sadly, premature, forcible foreskin retraction (PFFR) is a much more painful, serious, and potentially permanent injury than most parents imagine. It is also epidemic in Anglo-American medicine and, as the number of intact boys grows, the situation is worsening.

We speculate that only one in a thousand cases in the USA comes to our attention, and this could mean as many as 150,000 cases each year. Likely there are many similar incidents in other English-speaking countries (possibly an even higher percentage than the US because so many more boys outside the US are intact). Most parents have no idea that their child was injured or why.

Here is a typical complaint we receive:

Dear Doctors,

I have read on a mothering website that you handle complaints about retracting the foreskins of little boys. We kept our boy, Ethan, now six months old, uncircumcised because we know it is unnecessary, painful, and risky. Last week during a routine doctor visit, and before I could stop him, our paediatrician peeled Ethan's foreskin back all the way. It happened so fast there was nothing I could do.

Ethan screamed instantly, cried for hours, and has been restless and fussy ever since. There are now small circles, like cracks, around his foreskin, which ooze blood. His penis is red and swollen. Ethan is now unusually fussy as soon as his diaper is wet, so we think it must sting when he urinates. He screams when we change him or the diaper touches his penis. It just breaks my heart to hear him. He had no problems at all before this doctor visit.

The doctor told us that we must pull Ethan's foreskin back this way every day or at least at every bath, to prevent what he called 'adhesions' and to clean out the smegma that builds up there. He said that if we don't, our boy would need to be circumcised for sure.

Is all this necessary? I can't believe you need to hurt a boy to keep him clean. It makes no sense to me. I am very angry at what happened to Ethan. He was a very happy baby before this. Please help us.

What happened to Ethan is a clinically unnecessary injury and utterly inexcusable. Ethan's parents have exactly the right instincts, and with good reason. But to understand why, the reader needs some background.

The history of forcible foreskin retraction In the mid-19th century, many British and American doctors were hoping to convert childbirth and infancy into medical opportunities, thereby marginalising their ancient competitors—midwives and doulas. Thus the medicalisation of childbirth and infancy began in earnest.

Around the same time, other physicians promoted the notion that irritation or stimulation of sensitive tissue, like genital mucosa, caused disease to appear in a distant part of the body. They invented, for instance, the old locker-room myth that masturbation causes blindness. They called their pre-germ disease theory 'reflex neurosis'.

Of course this theory was false, but as well as conveniently blaming and shaming the patient for causing his own health problems, reflex neurosis spawned a whole breed of pseudo-medical interventions for children, including circumcision, clitoridectomy, and forced foreskin retraction. Aggressive cleaning, drying—even amputation—of sensitive, erogenous, genital tissue was, according to this theory, a way to discourage bodily exploration, thwart disease, and simultaneously promote 'moral hygiene'.

Especially widely publicised was the notion that a build-up of smegma, a protective secretion both boys' and girls' genitalia naturally produce, might cause unwanted stimulation, then termed 'irritation'. This stimulation might draw a child's attention to his penis (or her clitoris)—so goes the theory—which he or she might then touch. Even casual genital exploration by the child was thought to cause tuberculosis, insanity, blindness, idiocy, hip malformation, unusual hair growth, and dozens of other conditions.2 As late as the 1930s, some doctors advised parents to tie scratchy muslin bags, especially made for the purpose, on the hands of boys and girls, to prevent even inadvertent genital contact during sleep.

Parents were also advised to retract their boy's foreskin and scrub out any 'dangerous' secretions regularly, or have the boy circumcised so these could not possibly accumulate. Throughout the 20th century in all English-speaking countries, forced retraction for genital cleaning became standard medical practice. Millions of living, intact Anglo men, it is safe to say, were forcibly—and painfully—retracted as children.

An Australian medical historian recently published the following observation about the invented and erroneous myth of the need for rigorous infant male hygiene. He notes the irony that females only narrowly escaped similar treatment:

To appreciate the scale of the error, consider its equivalent in women: it would be as if doctors had decided that the intact hymen in infant girls was a congenital defect known as 'imperforate hymen' arising from 'arrested development' and hence needed to be artificially broken in order to allow the interior of the vagina to be washed out regularly to ensure hygiene.

—Dr. Robert Darby, A Surgical Temptation, The Demonization of the Foreskin and the Rise of Circumcision in Britain.

Lingering myths Surprisingly, this paranoid version of male infant hygiene has not yet died out. It still lingers, in various watered-down versions, passed around among generations of physicians and nurses folklorically, who then teach it to parents.3 While you read this, likely a professional at your local well-baby clinic is forcibly retracting a hapless little boy or advising the parents to do so at each bath. And we will see later that even the Royal Australasian College of Physicians' website, Paediatrics and Child Health Division, offers young parents antique and even potentially harmful advice on this subject.

Care of the foreskin Proper infant hygiene, for both girls and boys, is actually astonishingly simple:

'Only Clean What Is Seen.'

This means the boy (or girl) needs only warm water, gently applied to the outer, visible, portions of his or her genitalia. No soap is needed. No intrusive or interior cleaning of the genitalia of either gender is ever needed or desirable. Aggressive interior hygiene is destructive of developing tissue and natural flora, and is harmful as well as painful.

At birth the penis is anatomically immature. The foreskin is connected to the glans by a natural membrane, the balano-preputial lamina (translation: 'glans-foreskin layer'). This membrane is apparently nature's method of protecting the highly nerve-supplied and erogenous foreskin of the developing penis from irritation by faeces, the ammonia in urine, and invading pathogens.4 Although very different in structure, it can reasonably be thought of as the male's hymen, protecting the sexual organs during the years when they are not needed for sexual purposes. This membrane may take as long as 18 years or more to disappear naturally, allowing retraction.

Numerous studies have shown that the mean age for natural foreskin retraction without pain or trauma is around 10 years.5 Some men never seee their glans until they are in their 20s. Any age is normal; there is no need to see the glans prematurely. Indeed, pre-adolescent boys, like pre-adolescent girls, need no internal cleaning whatsoever, and to suggest toddlers need to be retracted at each bath, or should be taught to do so themselves, is antique, 19th-century, medical superstition.

Evolutionary biology Let us think like evolutionary biologists for a moment. If such cleaning were actually necessary, would any of us exist? Surely our forefathers would have died of infection in childhood, long before they could reproduce. Our primate predecessors were unlikely to head down to a nearby river every day to scrub their children's genitals. Nature would quickly eliminate those who needed such care. Only those tough enough to not require genital cleansing would have survived. We are those survivors.

In reality, urine, in the absence of a urinary tract infection, is sterile. The foreskins of infants, toddlers, pre-school and primary school-age boys are flushed out with this sterile liquid at every urination. No further cleaning is necessary. Mid-19th century English-speaking boys and girls did not suddenly require aggressive genital hygiene when their ancestors, for hundreds of generations, survived nicely on benign neglect.

Indeed the mucosal genitalia, like the eyes and mouth, are self-cleaning and self-defending. In evolutionary terms, it could not possibly be otherwise.

Culture influences medical training Male doctors born in America from the 1930s to the 1980s were almost invariably circumcised at birth. Consequently, they have no personal knowledge of the foreskin—a normal and highly specialised component of male anatomy. They are dependent upon whatever information they received in their medical training—from circumcised professors. Many American medical textbooks exported to Australia were written by circumcised doctors and lack even an illustration of normal male anatomy.6 Medical practitioners so minimally trained are unlikely to provide accurate information on proper care of a body part they do not possess and attend only occasionally.

(Anecdotally we at D.O.C. know there is an element of psychological compulsion attending the foreskin. Intact boys are a novelty to Anglo doctors who, in the USA especially, are mostly circumcised themselves or partnered with someone who is. The impulse to examine the child to explore what the doctor himself lost, or sees only rarely, seems irresistible even when there is no evidence of disease or infection.)

Better medicine vs hygiene hysteria A few modern English-language medical books correctly describe normal penile anatomy as Europeans understand it, and warn against tampering. Unfortunately, of the 40-odd medical, nursing, and parent-advice books the staff of D.O.C. has surveyed, only four give the proper advice. Mostly they parrot 19th-century pre-germ hygiene hysteria.

To understand the brief quotes from the best of these texts, it is helpful to know several medical definitions:

″ Prepuce—the foreskin of the male or the hood of the clitoris of the female.

″ Phimosis— Greek for 'muzzling': a narrowness of the opening of the foreskin, preventing its being drawn back over the glans, and usually due to infection or trauma. This is different from the normal attachment of the foreskin to the glans found at birth. Some clinicians use the term interchangeably to describe both conditions, but this is erroneous.

″ Paraphimosis—a tendency of an inelastic foreskin, once retracted, to become trapped behind the wide ridge of the glans.

″ Retractile—retractable, as an adult foreskin.

″ Pathologic—diseased, as opposed to normal physiology.

One reference text, Pediatrics,7 notes the correct timetable for foreskin retraction:

'The prepuce is normally not retractile at birth. The ventral [lower] surface of the foreskin is naturally fused to the glans of the penis. At age 6 years, 80 percent of boys still do not have a fully retractile foreskin. By age 17 years, however, 97 to 99 percent of uncircumcised males have a fully retractile foreskin.'

And Roberton's Textbook of Neonatology8 warns:

'Forcible retraction in infancy tears the tissues of the tip of the foreskin causing scarring, and is the commonest cause of genuine phimosis later in life.'

Avery's Neonatology,9 issues an identical warning:

'Forcible retraction of the foreskin tends to produce tears in the preputial orifice resulting in scarring that may lead to pathologic phimosis.'

Similarly, Pediatrics10 notes that phimosis or paraphimosis is '…usually secondary to infection or trauma from trying to reduce a tight foreskin…' And they add, 'circumferential scarring of the foreskin is not a normal condition and will generally not resolve'.

And even the American Academy of Pediatrics (who formerly discouraged breastfeeding and encouraged regular forced retraction of intact boys) has now changed its policy:

'Caring for your son's uncircumcised penis requires no special action. Remember, foreskin retraction will occur naturally and should never be forced. Once boys begin to bathe themselves, they will need to wash their penis just as they do any other body part.'11

The RACP—hygiene hysteria + dangerous medical advice? Unfortunately, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) website regurgitates old myths about foreskin retraction and the imaginary vulnerability of the intact child. The RACP also grossly misstate the timetable for natural retraction as well as imply the internal structure of the penis needs to be seen prematurely. They also imply that if a boy is not retractable at age four he may need medical intervention or surgery. This is unfortunately errant nonsense and fear-mongering, apparently intended to market genital surgeries including circumcision. They assert:

Physiological phimosis (normal narrowing of the foreskin that may make visualisation of the glans difficult during infancy) will normally resolve by the age of three to four years and requires no treatment. If pathological (ie, non-physiological) phimosis fails to respond to steroid cream/ointment applied to the tight part of the foreskin two to four times a day for two to six weeks, there is a reasonable probability that it will cause problems in the future and the child may well benefit from circumcision.

This notion is patently false, misleading, and suggests pathology after age four where none exists—unless created by prior forced retraction. Unfortunately, it reflects the training of Australasian medical professionals currently in practice.12 At four years of age, very few boys can retract their foreskins. Moreover, there is no need for them to do so, and like the hundreds of generations of their ancestors with natural genitalia, intact boys are at no unusual risk.

The RACP has been unduly influenced by what knowledgeable practitioners call the 'Gairdner Error'. In 1949, Douglas Gairdner, a UK paediatrician, published an influential article asserting that by age three, 90 percent of boys should be fully retractable.13 He based this guess on his limited clinical experience and, like other physicians of his generation, forcibly retracted, for hygiene reasons, boys who did not meet his timetable. He almost certainly examined boys whom others had forcibly retracted.

Though Gairdner's condemnation of infant circumcision almost single-handedly ended that practice in the UK, his erroneous timetable for natural foreskin retraction was widely publicised. Through the years, this error of anatomy has been carried over, unquestioned, from medical text to medical text and thence to parental advice books, without appropriate clinical proof. Since 1968, four European and Asian studies have proven Gairdner wrong.14 The RACP, however, mired in the medicine of 1949 and footnoting only Gairdner, has apparently yet to catch up with this accepted research.

So what will happen to little Ethan? Ethan's parents have every reason to be angry and concerned. Ethan's unnecessary forcible retraction risks, or has created, one or more fully avoidable outcomes, some of which may not become obvious for years. All will remain a worry:

″ Premature forcible foreskin retraction is uniquely painful because the foreskin is among the most densely nerve-supplied structures of the male body. Research shows that pain alone holds later psychological consequences.15

″ Likely the child now has an 'iatrogenic' (physician-induced) infection, caused by unnecessary tampering. Invariably forcible retractions are performed without surgical gloves or proper antisepsis, and the open wound becomes an immediate portal for disease.

″ His infection may worsen, leading to urethral ulceration, and, perhaps to urinary stenosis (blockage). Indeed, septic genital tampering is the likely cause of many avoidable urinary tract infections, themselves then used to justify post-neonatal circumcision.

″ The raw, bleeding surfaces, formerly separated by a natural membrane, might now grow together, causing unnatural adhesions or skin bridges that may, or may not, eventually dissolve.

″ His infection may leave scar tissue, which renders the foreskin inelastic, complicating adult hygiene and normal sexual functioning.

″ This inelasticity may create pathologic phimosis, an unnatural tightness of the foreskin opening, which might not fade with time and, ironically, may require medical intervention.16

″ The child with an inelastic foreskin may suffer periodic paraphimosis emergencies, or trapping of the foreskin behind the glans' corona when retracted. His glans may become strangled, trapping blood and causing swelling, which then must be released by hand.

″ The child may now endure painful nocturnal erections because of his compromised foreskin (four or five involuntary nightly erections are normal at all ages for both genders). This may interfere with necessary REM sleep and might even create sexual dysfunction in adulthood.

″ The child may become understandably reluctant to have any adult touch his genitals or bathe him.

Forcible retraction and circumcision You might already have sensed the connection between the historical marketing of circumcision and forcible foreskin retraction. Teaching youthful and trusting parents that an intact boy needs thoroughgoing internal hygiene at each bath helped to market circumcision, as it implied amputation might free the parents of this burden, unpleasant for them; painful for their son. Better—goes the argument—the immediate acute pain of circumcision than the periodic pain inflicted by parents over the years. And when the forcible retraction by parents did cause infection, or scar tissue, or adhesions, phimosis, or other problems, it was easy to blame the parents for inadequate hygiene or failing to choose circumcision, the 'sensible' option, to begin with.

Indeed, there is much anecdotal evidence that forcible retraction in the 20th century became a sort of retribution for non-compliant Anglo parents who declined circumcision for their newborn. The two, circumcision and forced retraction, have always been closely allied, and both create work for medical professionals, while leaving the intact boy alone to develop normally holds no economic benefit whatsoever. The false 'either-or' choice presented to parents for over 140 years has always been retraction and cleaning—or circumcision. The easy and more ethical European or Asian solution—leaving the child's genitals entirely alone—has only rarely been recommended in Anglo medical practice.

Post-neonatal circumcision A tendency to misidentify the normal connective foreskin membrane of toddlers and young boys as an abnormal 'adhesion' also leads to unnecessary post-neonatal circumcisions. Millions of older toddlers in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have endured painful, unnecessary, and psychologically challenging post-neonatal circumcision, with or without anaesthesia, based on this ignorance.

Misdiagnosis of the child's normal connective membrane is also the origin of the circumcision marketing mantra that 'he'll only need it later'. It is the direct source of many a family's story of their Uncle Bruce's painful circumcision at age six, of which he is only too happy to remind everyone. The implication is that circumcision is best done at birth, when, in truth, normal genitalia do not need fixing at any age, and never did.

Foreskin retraction for catheterisation …is never necessary. Sometimes, when a child has a fever of unknown origin, urinary tract infection (UTI) is suspected, though these are routinely over-diagnosed. (And ironically, many genuine UTIs are the direct result of unnecessary genital tampering by or on the advice of medical professionals—forced foreskin retraction being a prime example.)

The doctor might order the child catheterised to test for infection. Catheterisation itself poses a risk of pushing surface bacteria into the bladder causing a UTI, which always runs the risk of going further up into the kidneys. Better and less risky methods of testing for UTIs are available. Even when absolutely necessary, catheterisation can be done without retracting the foreskin. After threading the catheter through the preputial opening, the physician or nurse need only gently probe to find the inner urethral opening by 'feel'. Even partial retraction should not be needed. But especially in the US, where so many are circumcised and normal male genitalia get minimal respect, this conservative protocol has become a lost art.

Immediate first-aid for forcibly retracted intact boys Not all forcibly retracted boys develop the problems we detail, and millions have eventually recovered from the physical results of forcible retraction by the doctor or on doctors' orders. Of course, millions did not fully recover and bear permanent, lifelong problems that they may not even recognise as an injury. Moreover, the medical community has only a limited understanding of the psychological effect of unjustified pain imposed on a boy's genitals by his caregivers.17

If your child has been forcibly retracted, some experts suggest creating a barrier between the raw surfaces by gentle separation and the use of an oil-based cream to prevent the surfaces from adhering abnormally. But this is also very painful for the child, psychologically challenging, and holds no guarantee of success.

Other experts suggest that it is better, physically and psychologically, to leave the boy alone and allow his natural healing powers to take over. Studies do show that adhesions from circumcision, for instance, tend to resolve spontaneously.18 This theory holds that the psychological effect of further, repeated, painful, and traumatic handling of the boy's genitalia may not be worth the effort or risk.

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers, and no studies show which method is best, as the extent of this unique injury has not been admitted, let alone widely recognised.

Certainly the parents of a forcibly retracted boy are now obliged initially to monitor the child for infection. Additionally, the parents must be prepared in advance for paraphimosis emergencies for which the older forcibly retracted child is at unique risk. After puberty begins, the boy himself must determine his ability to retract his foreskin or whether he has adhesions that have not receded as he matured.

The best medicine is, of course, prevention. Parents should absolutely forbid any retraction before it occurs by making their wishes known in advance, in no uncertain terms, in writing, perhaps with a copy of this article in hand. Make your wishes a formal part of your child's chart. Ask yourself: if my medical professional does not grasp this fundamental anatomy, what else does he or she not understand?

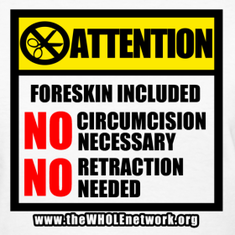

D.O.C. offers colourful nappy stickers for parents to use that read 'I'm Intact; Don't Retract!'. This prompts a non-threatening discussion with your child's provider. Better to momentarily irritate—or educate—your family physician or nurse than to injure your son for life.

And, if you are ignored and your child is forcibly retracted despite your warning—it can happen in seconds—you should report the offending physician or nurse to your medical licensing authorities, supplying all the details. Or contact our physicians' group to help you. There is no charge for our intercession, though donations are appreciated.

If your provider understands and respects your child's natural anatomy, please share his or her name with us. We are always on the lookout for well-educated, ethical, 'foreskin-friendly' physicians and nurses, worldwide, to whom we can refer, with confidence, when parents of intact children of any country inquire.

Remember—you have no duty to massage the ego of a poorly educated medical practitioner. Protect your child instead!

John V. Geisheker, JD, LLM, a native of New Zealand, is currently the Executive Director of Doctors Opposing Circumcision (DOC), based in Seattle, Washington. A law professor by education, he has been a litigator, law lecturer, arbitrator, and mediator, specialising in medical disputes, for 27 years. Most recently he helped to defend 'Misha', a 13-year-old facing an involuntary, non-therapeutic, religious circumcision, a cause now headed to the United States Supreme Court. Mr. Geisheker is married and the father of two grown children. He is proud that his native New Zealand fully abandoned medicalised infant circumcision in the 1960s as unethical and unnecessary.

John W. Travis, MD, MPH, completed his medical degree in Boston and a residency in general preventive medicine at Johns Hopkins University. He subsequently founded the first wellness centre in the US, developed the first Wellness Inventory (now available online), and co-authored the Wellness Workbook. Realising, in 1991, that how children are raised has far more influence on their later wellness than other any factors in our lives, he expanded the focus of his work to Full-Spectrum Wellness to include infant wellness, along with co-founding The Alliance for Transforming the Lives of Children (aTLC.org), and authoring Why Men Leave, The Epidemic of Disappearing Dads, first published in byronchild (now Kindred) in 2004, which is now becoming a book. He now lives in Mullumbimby, New South Wales.

Resources:

Doctors Opposing Circumcision, Seattle, Washington: www.DoctorsOpposingCircumcision.org

(Endnotes)

1 D.O.C. follows up all such complaints with a scientifically referenced 10-page letter to the physician or nurse, detailing the correct medical protocol, and if the parents agree, files a formal complaint with the relevant licensing authority.

2 Szasz, T. Remembering Masturbatory Insanity. Ideas on Liberty, 50: 35-36 (May), 2000, The Foundation for Economic Education, Irvington-on-Hudson, NY.

Gollaher, DA. Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery. Basic Books, 2000.

3 Hill, G. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. MJA 2003;178(11):587. http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/178_11_020603/matters_arising_020603-1.html

4 Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ. The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-5.

Cold CJ, Taylor JR. The prepuce. BJU Int 1999;83 Suppl. 1:34-44.

5 Øster J. Further fate of the foreskin. Arch Dis Child 1968; 43:200-3.

Ishikawa E, Kawakita M. [Preputial development in Japanese boys]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004;50(5):305-8.

Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose? Ugeskr Læger 2005;167(17):1858-62.

Agawal A, Mohta A, Anand RK. Preputial retraction in children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2005;10(2):89-91.

6 Harryman, GL, An analysis of the Accuracy of the Presentation of the Human Penis in Anatomical Source Materials, in Flesh and Blood, Perspectives on the Problem of Circumcision in Contemporary Society, eds. Denniston, Hodges, and Milos, Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers, NY, 2004.

7 Rudolph, AM, and Hoffman, MD. Pediatrics, Appleton and Lange, 1987, 18th ed. p1205.

8 Rennie, J, and Roberton, NRC. (eds), Care of the Normal Term Newborn Baby, in Textbook of Neonatology. 3rd edn., Edinburgh, Churchill Livingston, 1999:378-9

9 MacDonald (ed). Avery's Neonatology: Pathophysiology and Management of the Newborn, Lippincott, 2005:1088.

10 Osborne, L, DeWitt, T, First, L, Zenel, J. eds, Pediatrics. Mosby, 2005:1925.

11 AAP Bulletin, Care of the Uncircumcised Penis, American Academy of Pediatrics, 1999. Available at: http://www.cirp.org/library/normal/aap1999/

12 RACP Paediatrics & Child Health Policies, Circumcision at: http://www.racp.edu.au/index.cfm?objectid=A4268489-2A57-5487-DEF14F15791C4F22

13 Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin: a study of circumcision. Br Med J 1949;2:1433-7.

14 Øster J. Further fate of the foreskin. Arch Dis Child 1968; 43:200-3.

Agawal A, Mohta A, Anand RK. Preputial retraction in children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2005;10(2):89-91.

Ishikawa E, Kawakita M. [Preputial development in Japanese boys]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004;50(5):305-8.

Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose? Ugeskr Læger 2005;167(17):1858-62. See translation of abstract at: http://www.cirp.org/library/normal/thorvaldsen1/

15 Taddio A, Katz J, Ilersich AL, Koren G. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain response during subsequent routine vaccination. Lancet 1997;349(9052):599-603.

16 Spilsbury K, Semmens JB, Wisniewski ZS et al. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. Med J Aust 2003;178(4):155-8.

Rickwood AMK, Walker J. Is phimosis overdiagnosed in boys and are too many circumcisions performed in consequence? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1989;71(5):275-7.

Griffiths D, Frank JD. Inappropriate circumcision referrals by GPs. J R Soc Med 1992;85:324-325.

17 Anand KJS, International Evidence-Based Group for Neonatal Pain. Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:173-180.

18 Ponsky LE, Ross JH, Knipper N, Kay R. Penile adhesions after neonatal circumcision. J Urol 2000;164(2):495-6.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed